“There’s a keen difference between working with National Geographic and being an independent photographer”, says Nathan Benn, renowned photographer, former director of Magnum Photos. After nearly 20 years as a National Geographic photographer, reporting on many regions around the world including Netherlands, Dead Sea, South Korea, the Mississippi River and Jewish Diaspora, among others, Benn is now exhibiting his work of Kodachrome Memory American Pictures at the Leica Gallery in Los Angeles. We had the opportunity to talk to him about this exhibition and experience.

Part of Nathan’s desire to create this exhibition was born out of an internal search of artistic identity. It evolved from his many years of shooting for National Geographic and re-discovering thousands of pictures to working in the field. “It was always about assignments and usually under very general terms. The assignment brief would be something like ‘Please photograph the state of Florida’. You were sent out the door with all film expenses and then return months later with the film.” Benn says.

He continued explaining the nearly mechanical process of delivering these magazine-ready images. “In the field we were shooting mostly 35 mm film, with Leica Rangefinders and Nikons. The film would be sent undeveloped back to the office in D.C., processed by Kodak, then returned to [National] Geographic and a picture editor would look at the film and pick out the pictures that would potentially be publishing material.” Benn graduated in 1972 and immediately started working for National Geographic. Not knowing anything about art history, his photographic taste was formed by the classic post-war humanistic photography defined by Eugene Smith, Leonard Freed, among others. A true admirer of photojournalism, he initially wanted to work for Life magazine, photographing important events.

Imagine removing the photographic dust of more than 12,000 pictures, buried in the nostalgia of those multiple years of work. “The rest of the pictures would go into the little cardboard boxes. So, I would have to follow the picture editor’s judgement regarding the selection of the images they would use. If I took a picture in 1973, I wouldn’t see it. It would be seen by an editor. Nine out of ten pictures, I wouldn’t see them, because the picture editor would be the one that would select them. That was typical of the way I worked.”

Therefore, going 30-40 years later, into the early 2000’s, all his pictures were returned and stored in a warehouse. Just until after leaving Magnum photos in 2003, Benn had the opportunity to revisit these images and develop the book and exhibition.

“When I started shooting in 1991 after leaving National Geographic, I was interested in something else. I was interested in new media. Then for the first time, in 2003, I wasn’t going into an office. I had the time and interest to look at my pictures. I didn’t know where that would lead.”

Benn’s first priority was simply to throw away what didn’t work. The second campaign of reviewing all of these pictures was deciding what was going to be digitized. Around 12,000 pictures were digitized and made available for stock photo distribution. Then, around the year 2010, Benn started to observe within these newly re-discovered pictures themes. Themes that would later transform into a book and exhibition.

“My goal was to surface and identify the pictures and coordinate so that I could define my personal viewpoint as a photographer, not as a National Geographic photographer, but as Nathan Benn. I needed to forget about being the photographer in the field. I needed to separate myself from that,” Benn points out. He adds: “When you’re shooting, your judgment is blurred by the fact that you are in the moment itself. The timeliness of the subject of that particular subject, the degree of difficulty, your personal stories.”

Considering there was no color documentary photography back then, Benn later became known for his work in the field. “There were a few photographers shooting in color,” he adds, “but their work in color was hardly known. They had a hard time selling color. Because the black and white style was way more popular.”

Something that influenced his artistic perspective and influenced his color photography, especially in the late 1970’s, was painting. Benn started looking at painting in the 1970’s, mostly Italian Renaissance. “I would be in Paris or Prague and clearly, they had a lot of paintings in museums, because photography wasn’t a global art form yet.” Benn began reading about Renaissance painting more in depth, and developed an admiration for this art style. He illustrates his painting inspiration by saying “the arrangement of reds, and blues and greens among these paintings was trying to tell a story whic was unique. Looking back to my photographic career, I feel that same sense of trying to depict a pleasurable, eye-watering pictures.”

When talking about the book cover, he refers to the image of the women standing elegantly in front of the soda machine. “When I shot it, I didn’t think it would be a cover of a book 30 years later. But when I saw it again, I thought immediately, it is a great photo.” Trying to understand his admiration for this particular photograph, he recalls a visit to the Cleveland Museum of Art and looking at some Renaissance paintings. “There was a picture of a saint with a halo and I said, ‘Now I understand why I like that picture!’.” In terms of the composition and the direct view, of the framing of the head by the Coca-Cola sign, as well as the role of the garments, the picture suggests that same halo effect. Benn underlines he certainly didn’t make that connection back then, or even when selecting it for the book cover. But it tells you a lot how those artistic connections made the photographer appreciate this picture so much.

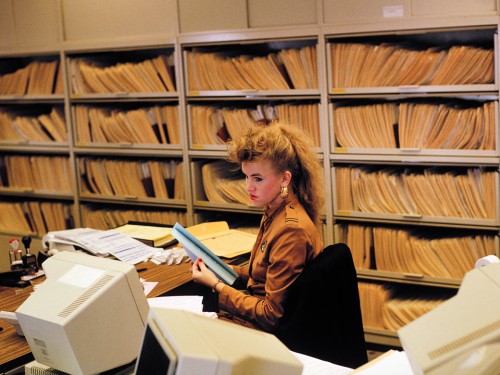

Taking a photo of a law office can be very dull. Benn explains, “You say to yourself, what am I doing here? But looking at it now, I feel this picture is truly authentic.” Some may think otherwise, but Nathan highlights the difficulty behind these situations when trying to take the pictures, especially since the subject nor the situation were clearly defined. However, they really do talk about that specific moment in time.

Nathan Benn has carried his Leica camera for many years now and talks about his experience with the heritage brand. “We were fortunate enough to have the best gear available, including the Leica M4, or M6. I am very content about this period where I worked as a photographer, seeing analog photography reach its peak right before transitioning to digital. It was a great experience and this exhibition can really show the authenticity of a timeless America, all through the Leica lens.”

Talking about his preferences, he concluded by talking about the versatility in Leica cameras: “My Leica would always be the least intrusive, with a quiet shutter. Even though it took me sometime to get used to the rangefinder, I could use it under almost every circumstance. I would take my best pictures when I was not even thinking about my gear, and using my Leica camera would simply feel like second nature. Almost like an automatic response.”

Thank you Nathan!

Nathan Benn’s Kodachrome Memory American Pictures Exhibition will be open at the Leica Gallery in Los Angeles until December 7th, 2015. Please visit their website to know more.

For more information about Nathan Benn, please visit his website or look online for his book.

Comments (4)