Guillem Valle first became interested in documentary photography at the age of 14 when he traveled to Sarajevo an an art student exchange program in 1998. In 2003, he began to work with local newspapers documenting the social movements in Barcelona, all the while mainlining a personal agenda. Over the years, he has worked on many stories including Kosovo’s Independence, the Uygur minority in Western China, PKK fighters in the mountains of Northern Iraq, the war in Lebanon, the gold mines in Congo, the pre-independence situation in South Sudan among others. Beginning in 2010, he based himself out of Bangkok, Thailand and started working on issues around South East Asia. At the end of 2011, he moved to the Middle East to cover the last months of the war in Libya the second uprising in Egypt or the situation in Syria. Currently based in Barcelona and Bangkok, his work is represented by Corbis. His reportage on the Kurds in Syria can found in the latest issue of LFI.

Q: How did you first become interested in Leica?

A: Well, I’ve been always attracted to Leica. I started shooting while still everybody was using analogue and one day a friend of mine loaned me an M6. I liked the feeling of shooting with this small camera very old looking but yet knowing that the quality for the lens was superb. Leica has always bin a bit out of my budget though.

Q: How would you describe your photography?

A: Despite the fact I have done many types of photography in order to survive, documentary photography has always been my main interest and the main axis of my work.

The more I grow up the more I’m sure of what do I want with photography. It’s been a long process, which I’m still in. I’m now more interested in not just telling a fact or an event but also in transmitting the feeling or the sensation of being there, living that moment.

What I’m trying to achieve is that every picture has two messages. The first would be describing a fact, an event or an idea. The second one would be transmitting the sensation or the feeling you might have by being there and above all, a reflection. This is something much more subjective and I think that belongs much more on the viewer’s interpretation.

I’m also interested in making images that, because of the expression, the light or the content, can last in time, become immortal. I know it sounds pretentious but at least this is what I try to keep in mind recently, while shooting any story.

Q: Did you have any formal education in photography, with a mentor, or were you self taught.

A: I studied 3 years at the IEFC (Institut d’Estudis Fotogràfics de Catalunya) in Barcelona then I kept teaching myself by watching other photographers work. I had some mentora but what taught me more was working on the field with other colleagues and the often 24 hours discussion that erupted while with them… Most of the little I know, I learned from my friends…

Q: Was there a photographer or type of photography that influenced your work or inspired you?

A: At the very beginning, I was amazed by Nachtwey’s work and his character., I think both things are related. Then I discovered the guys at Magnum Photos and the way the have always mixed art and documentary photography. That influenced me the most, I think.

Now a days, I discover some new photographer I didn’t know but I like a lot and influences me pretty much.

I think is good to keep searching authors that might make you rethink your photography and make it evolve. And moreover, I thinks it is good to watch art and cinema, not just other photographers.

Q: When did you first become interested in photography as a mode of expression, and art form, a profession?

A: I think it was in a very naïve way. I went to Sarajevo in 1998 for a student exchange program. At that time, the city was still completely destroyed, NATO tanks were everywhere and people just started to return to their homes some months ago.

I started shooting instinctively with a camera I borrowed from my father. While there, I liked the feeling of being in an important place, portraying the situation. That simple. Afterward I started to develop much more the reasons why I wanted to do this job.

Q: How would you describe your photographic approach in shooting this Kurdish reportage?

A: First of all, I wanted to create a visual document of what is going on in that part of Syria. But as I told you before, I wanted not just to explain a story in a very descriptive way but to transmit also the idea of being there.

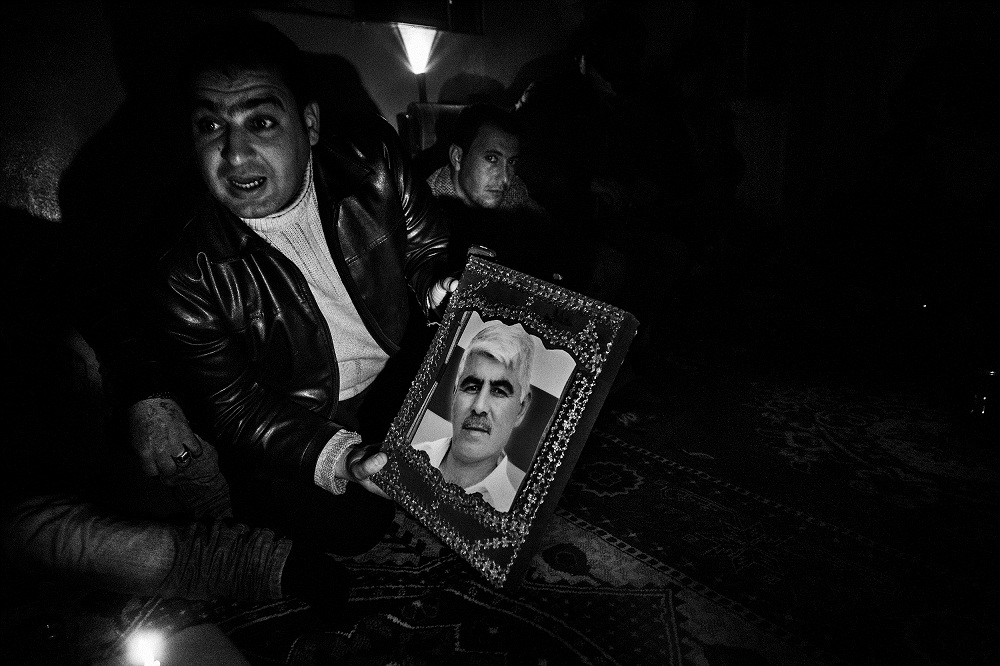

This story has gone pretty much unnoticed, (as much of the Kurdish issue in general), that gave me the sensation of something being hidden. While there, I discovered that most of my photographs were being taken in the darkness due to the lack of electricity. I wanted to use that lack of light to enhance that “hidden” sensation.

Q: What was your ultimate goal, or what did you hope to achieve, with shooting these images?

A: My main goal is to give another point of view of the war in Syria. The point of view of the Kurds who have stand up against the regime in their own way and that has brought a lot of troubles with rebel forces. In my opinion, Kurds have a very plausible political project that they are actually putting in practice right now and they have a lot to contribute to a possible post-Assad Syria.

At some point, I read something saying that the Kurds in Syria were supporting Bashar, something that I couldn’t believe. I started investigating and I soon realized that was totally wrong and that the very little information was being published were not very accurate. That leaded me to go there, try to understand, and try to make others understand.

On the other hand, it’s been 12 years now that I’m working in a long-term project about nations without state and this story is going to be a very important chapter of that project.

Q: Do you consider your photos to be a specific genre?

A: Yes, documentary photography.

Q: What cameras/lenses/equipment did you use to shoot this series?

A: I was using a Leica M9 with a 35mm f/2 Summicrom.

Q: Did you want the reader to have a specific reaction to these photos? Did you want to elicit a certain emotion from the viewer?

A: Yes, beside my first intention which is make others to know and understand a certain situation or event, I wanted also to transmit them that feeling of something is going on but is being hidden at the same time.

Q: What was the inspiration behind the idea to do this series? Basically, where did the idea come from?

A: Well, as I said before, I realized that this story was not very broad told so I wanted to drag people’s attention to it while I was trying to understand it at the same time. On the other hand, Kurdistan is a very important chapter of my Stateless Nations project so everything matched.

Q: I noticed that the images are all in black & white. Do you always shoot in B&W and is there a reason behind shooting this reportage in B&W?

I pretty much like shooting in black and white. I feel more comfortable. I think black and white gives you more options in order to evoke sensations. However, I shoot color too. I think that every story must have it’s own language though to me, it’s hard to figure out.

Q: Is there any Leica equipment (the new M, Monochrom, etc) that you would like to get your hands on to try?

A: Yes, the new M and the 35 mm f/1,4 Summilux!

Q: Photographers often go into combat zones or on humanitarian missions and show what is happening to the people involved. Do you think photography can change the world? Make a difference in the subjects’ lives?

A: I don’t think photography can change the world though I believed it when I started. You might be lucky and have some sort of direct impact on subject’s lives but I think is something very random and I’m not even sure.

However, I think it’s important to document what’s going on in our world cause at the end, we all are creating memory. And I say we, not just referring to other professionals but referring to everybody in general cause nowadays, many people has a camera and knows how to use it.

What I mean is that documenting the story while it’s unfolding helps to rise awareness and opinion among people. The fact of creating a document helps also to rise knowledge among the upcoming generations. At the end, I think journalism (good journalism) can help to make people less stupid and less prone to manipulation.

Q: Any other projects coming-up you’d like to share?

A: I think I’ll be working in this story for a while. I’m planning a third trip there though I can’t give many details yet.

As I said before, I’m working on a long-term project that investigates and documents the nature of Stateless nations around the world so most likely my next projects will be in the Middle East or eastern Europe. I’m preparing a Multimedia about it, a book and also thinking of a documentary film so I have now a lot of desk work ahead.

Thank you for your time, Guillem!

– Leica Internet Team

Please find Guillem’s full reportage in LFI 3/2013. Also available for the iPad. Find a reading sample here. Watch a video on the reportage too. To see more of Guillem visit his Facebook and Tumblr pages.

Comments (9)